Projects

FuTRES is designed to be expandable, and we expect many novel uses for trait data to come from its implementation. We present here a set of example use cases that we will pursue, using the results both to inform process-based research and to publicize the presence and utility of FuTRES. These use cases focus on mammal data, because we have chosen to focus on this lineage for our initial data ingestion.

FuTRES will not be limited to mammal data, however, and we will welcome data from domain scientists across the tree of life. In the end, many other analyses are also possible, such as the examination of processes that control miniaturization and gigantism across vertebrates, testing whether deforestation has led to evolutionary changes in bird or insect wing-aspect ratio, determining whether pre- and early historic fishing significantly reduced trophic levels and disturbed ocean ecologies, and testing hypotheses about the limits of allometric scaling in relation to overall body size across lineages of vertebrates, as a few examples.

Bergmann’s Rule

Lead: R. Guralnick

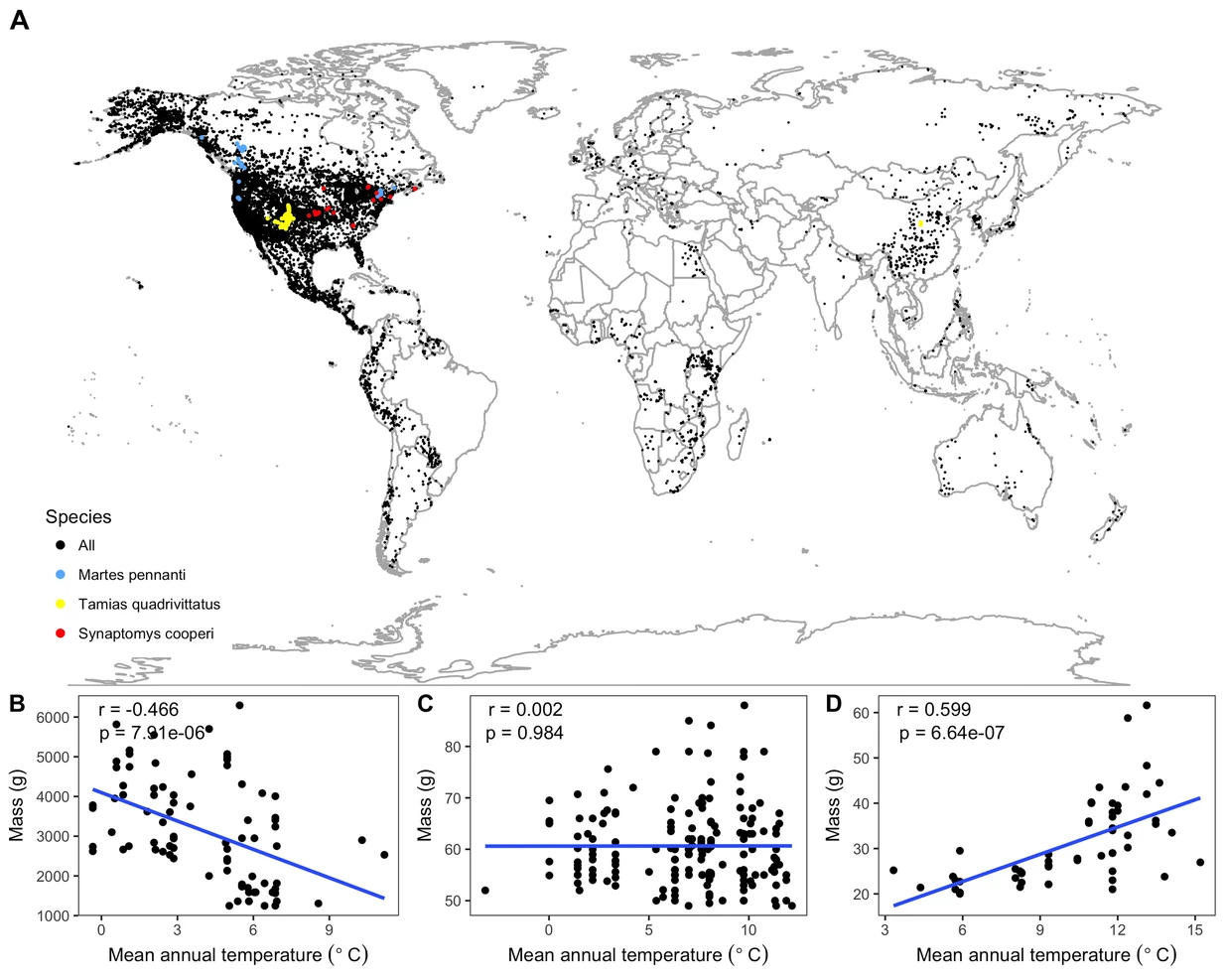

Bergmann's rule is a widely accepted biogeographic rule that individuals within a species are smaller in warmer environments. It provides a predictive framework for understanding potential response of species in the face of climatic changes. Co-PI Guralnick is investigating whether niche characteristics of species are predictive of relationship between abiotic factors and intraspecific body variation. To best do this, it is critical to aggregate specimen measurements from fossil and modern species and handle direct and inferred measurements of body size. Guralnick will develop use cases focusing on body size variation in small mammals with exemplary sampling in the modern and fossil record (e.g. deer mice) and develop new model frameworks for integrating fossil and modern body size datasets.

See recent publications related to this work.

Equid Locomotion

Lead: R. Bernor

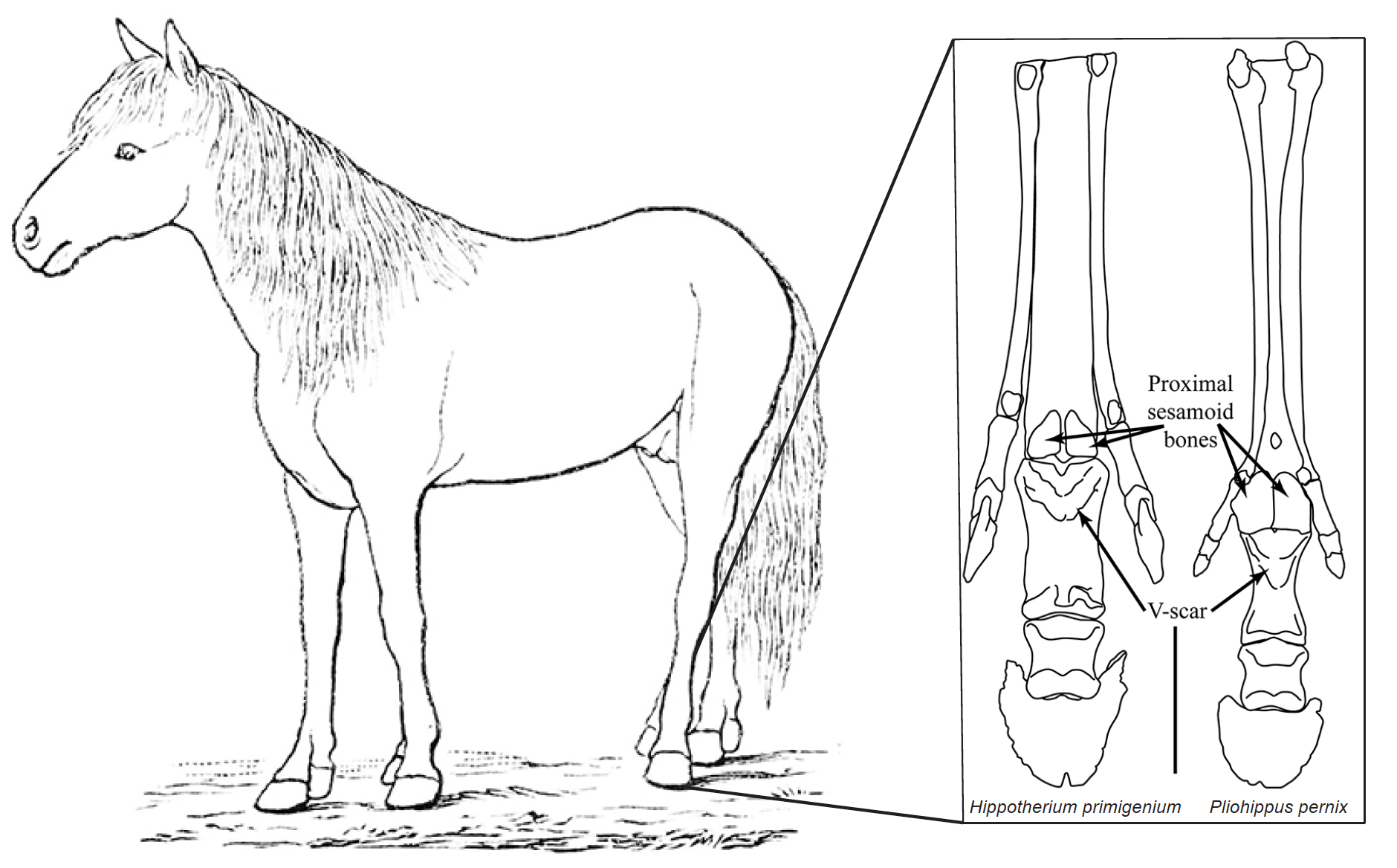

The primary activity overseen by Co-PI Bernor will be the ingestion and analysis of his data on equid distal limb elements. These data have been used to characterize the relationship between varying proportions of distal limb elements and locomotion and habitat. While previous research has revealed a great diversity of size and limb proportions in extinct horses, the ingestion into FuTRES offers a unique opportunity to compare these ‘wild’ pre-human-impact data to the distribution of limb proportions in modern equids of North America. Co-PIs Davis and Emery will work to ingest equid limb proportion data from the archaeological record of the USA. In this way, we can test the hypothesis that existing feral horses have adopted ecological roles analogous to the wild horses that were lost in the megafaunal extinction ~13,000 years ago.

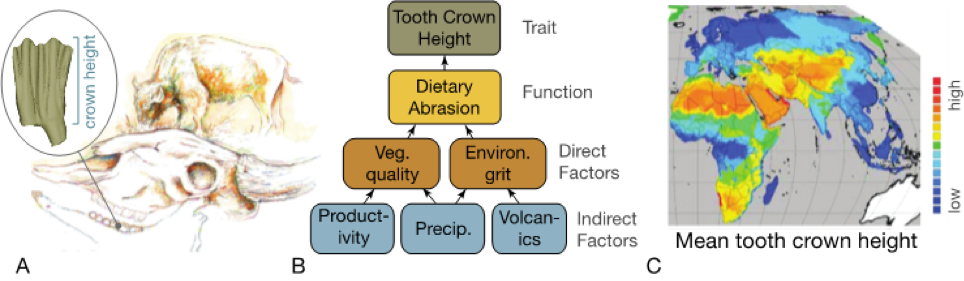

Hypsodonty and Crown Type

Lead: R. Bernor

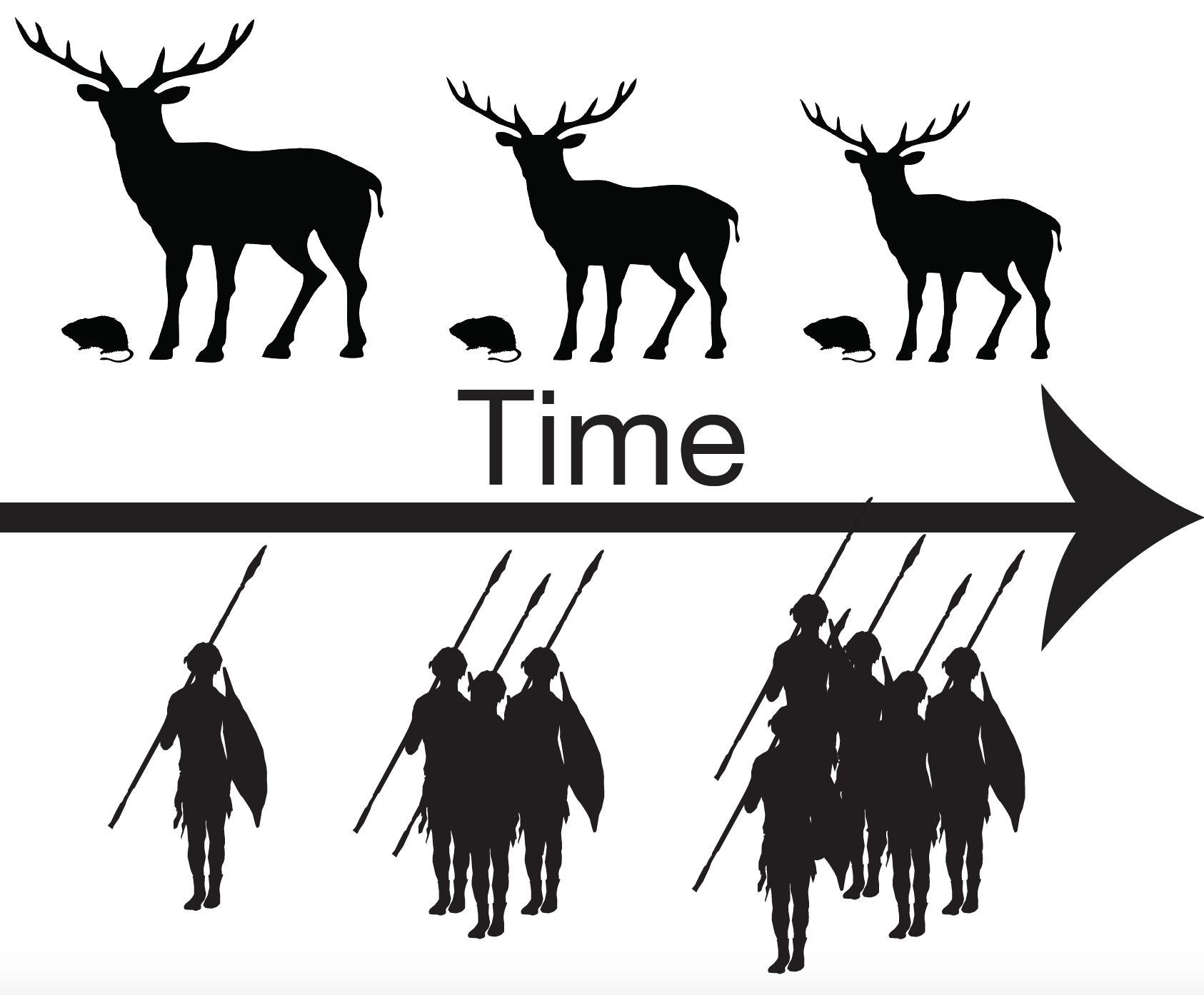

Using Prey Body Size Data to Track Human Impact

Lead: K. Emery

Mammalian Reproductive Life History

Lead: B. McLean

Determining the drivers of variation in mammalian life histories is essential for effectively monitoring global change responses of these taxa. Our goal is to develop individual-level databases of reproductive and life history traits from extant mammals (mostly rodents) and link these to environmental drivers of trait variation. FuTRES data represents a gold standard for this work because it is collected at the specimen level and easily linkable to environmental conditions at the place and time of mammal captures.

Testing Allometric Methods

Lead: N. De La Sancha

Allometry has been used in the context of three different phenomena (ontogenetic, static, and evolutionary allometry); evolutionary allometry have been valuable to predict size for across species for both extant and extinct fauna.

Most allometries assume a power function relationship for prediction, are there other functions which might be better predictors across taxa?

We compiles a dataset across the mammal tree of life to test various functions to test allometries in mammals.

Determining Best Predictor for Body Size from Limb Elements

Leads: J. Saarinen and R.L. Bernor

We tested published dental and limb bone measurement -based regression equations (Janis 1990, McFadden and Hubert 1990, Scott 1990, Aberdi et al. 1995) for estimating body mass of horses (Equidae) by comparing how accurately the resulting body mass estimates from these equations for modern zebras (Equus quagga and E. grevyi) match published mean body masses of these species (Kowak 1999). Based on % prediction errors of the estimates from different skeletal measurements, we created a “best practice” -scheme for estimating equid body masses in terms of the choise of skeletal elements that most accurately estimate body mass in equids. Metapodial articular and mid-shaft widths were found to be among the best and most frequently available measurements, and they predict body mass more consistently than dental measurements, so they have the priority in equid body mass estimation. Of dental measurements, first upper and lower molar lengths provide the best body mass estimates for modern zebras. The work has been done (as thoroughly as published records allow), so not much further input from FuTRES is necessary, except in the form of discussion.

Trait Variation in Mammals across Size, Climate, and Life History

Lead: M. Hantak

Animal body size is an important morphological attribute that is tightly linked with physiology, behavior, and ecology. Previous work has demonstrated variability in body mass and length correlations between small and large mammals. However, these relationships have never been examined in a single modeling framework that encompasses variation in environmental conditions or functional traits. Using the data ingested into FuTRES, we aim to examine body mass and length allometries among hundreds of mammals across a range of relative body sizes, while accounting for climatic conditions and life history traits.

Best Practices for Developing and Reporting Allometries

Lead: M.A. Balk

Biologist (modern and paleo) tend to use mean species' body size in studies. However, these values have been determined possibly from a small sample size, or are old and do not represent population or species trends. We use data ingested into FuTRES to recalculate species' body size distributions and further show how to best report these allometries so that a range of a trait can be recreated.

Cleaning Big, Messy Data

Lead: M.A. Balk

Despite labs having standards for trait collection, these standards may not be the same across labs or may be errorenously entered into a data store. Using FuTRES as a case study, we develop method standards for cleaning big, messy data without making assumptions about ranges for species' traits based off the literature. Additionally, we will make these functions available for other data collectors to test.

Tool Paramaterization for Predicting Body Size

Lead: E. Davis

Linking traits from the carcass down to the osteological traits of interest

Leads: K. Emery and S. Pilaar-Birch

A significant hurdle to deep time research on changing body sizes is the disconnect between body size metrics derived from live animals and carcasses by neontologists, and those derived from skeletal allometry by paleontologists and zooarchaeologists. Allometric formulae to estimate body mass or more specific features such as limb length are often based on small localized datasets for which important ancillary data is missing including not only age and sex, but also other aspects that can affect the relationship between skeletal and whole body metrics such as pregnancy status, habitat characteristics, and season of death. Institutions curating osteological materials from modern animal specimens are in a unique position to provide matching data on carcass and skeletal metrics from specimens for which much of the ancillary data is also available in collection field notes. We propose to compile such data and to evaluate not only the basic relationships between skeletal element dimensions and body mass, but also to understand more specific relationships between body portions and their skeletal framework. For example, by gathering large amounts of data on the dimensions of various foot bones and the traditional “foot length” metric taken on cervid carcasses, we could better understand changes in deer foot shape over deep time by linking paleontological, zooarchaeological, and modern metrics.

Recapturing Legacy Trait Data from Paper Records

Leads: Nicole, R. LeFrance, K. Emery, R. Guralnick

Legacy trait data from analysis of museum specimens is often available only as paper records or at best, as pdfs of such paper records. Early databases provided only limited capacity for recording what was considered “ancillary” data and so even when museum databases are published, they often lack the associated trait data that remains in paper archives. In the Florida Museum Environmental Archaeology Program archives we curate well over 100 massive binders of old green-stripe computer printouts that represent the only remaining record of years of metric data gathering from the 1940s to 1970s. Dot matrix printed in skewed tables in faded type on joined oversized sheets, these data are difficult to extract from the paper records but as part of the FuTRES project, we are using library archive scanners and advanced OCR technology to extract the data and connect the metrics to our specimen records.

Osteometric Traits Trace Early Turkey Husbandry in Mesoamerica

Leads: K. Emery, E. Thornton

Although the FuTRES project is not yet accepting non-mammalian trait data, we are eagerly anticipating submitting linear and geometric morphometric data gathered by the Mesoamerican Turkey Domestication Project from turkey specimens representing the entire history of turkey domestication from earliest husbandry to modern heritage breeding. Our data reveals not only some trajectories of body shape size that clearly trace a shift from breeding for feather production to meat production, but more vitally, highlights the enormous variability in breeding practices during the earliest stages of domestication. We link this metric data to that from genetics, isotopes, and paleopathology, providing overlapping evidence of early experimentation. To more fully contextualize the morphological changes associated with early domestication, we plan to also link our archaeological data to paleontological and neontological osteometrics and allometrically derived body size data via the FuTRES platform.

Testing body mass estimate equations for modern zebras – implications for body size evolution of Equus in the Old World Pleistocene

Leads: J. Saarinen , O. Cirilli, K. Meshida, F. Strani, R.L. Bernor

We tested published dental and limb bone measurement-based regression equations (Janis 1990, McFadden and Hubert 1990, Scott 1990, Alberdi et al. 1995) for estimating body mass of horses (Equidae) by comparing how accurately the resulting body mass estimates from these equations for modern zebras (Equus quagga and E. grevyi) match published mean body masses of these species (Kowak,1999). Based on % prediction errors of the estimates from different skeletal measurements, we created a “best practices” scheme for estimating equid body masses in terms of the choice of skeletal elements that most accurately estimate body mass in equids. Metapodial articular and mid-shaft widths were found to be among the best and most frequently available measurements, and they predict body mass more consistently than dental measurements, so they should have priority in equid body mass estimation. Of dental measurements, first upper and lower molar lengths provide the best body mass estimates for modern zebra. As a case study, we estimated the body mass of Pleistocene equids from Asia, Europe and Africa, and the Pliocene North American Equus simplicidens sample from the Hagerman Horse fauna (southern Idaho) using these three metapodial measurements. We discuss the body size evolution of Pleistocene Old World horses, and how it relates to changes in diet and paleoenvironments. The following fossil species were included in this study: Equus simplicidens (3.7-2.8 Ma), E. eisenmannae (2.55 Ma), E. livenzovensis (2.6-2 Ma), E. major (2.6-1.8 Ma), E. stenonis (2.4-1.8 Ma), “E. senezensis” (2.2-2.0 Ma), E. stehlini (1.8 Ma), E. koobiforensis (1.9 Ma), E. oldowayensis (1.8 Ma), E. sp. 1 and E. sp. 2 (Dmanisi, 1.8 Ma), E. altidens (1.6-0.6 Ma), E. suessenbornensis (1 – 0.6 Ma), E. mosbachensis (0.7-0.5 Ma) and E. ferus (0.5-0.01 Ma).

Re-discovering Equus stenonis Cocchi, 1867; new insights on its morphology, taxonomy and evolutionary role in modern zebras

Leads: O. Cirilli, R.L. Bernor, L. Rook

Equus stenonis Cocchi, 1867 is one of the most important equid species in the Early Pleistocene of Europe and Eastern Asia. This species, known since the second half of the XIX century, has been recovered from many fossiliferous localities and it is believed to be a probable ancestor of the modern zebras. Nevertheless, several scholars have studied this species, stating various opinions about species-level taxonomy and phylogeny of Equus. One of the most iconic features of this species has been its subdivision in several subspecies, including: E. stenonis vireti, E. stenonis guthi, E. stenonis senezensis, E. stenonis guthi, E. stenonis olivolanus and E. stenonis stenonis). This has led to confusion about the evolutionary relationships of Old World Equus. We have undertaken analyses on the most important Early Pleistocene Equus bearing localities of Europe, including Saint Vallier and Senèze (France), Olivola, Matassino and the Upper Valdarno Basin, Italy, in order to quantify the intraspecific variability of each locality sample. We are carrying out analyses on a large sample of cranial, mandibular, cheek tooth and postcranial specimens utilizing a suite of analytical analyses. These results will be integrated with a current understanding of climate change in the early and middle Pleistocene of Eurasia and Africa. Preliminary results suggest that there is substantial intraspecific as well as interspecific variability for each subspecies. Of particular interest is the overlap in variability ranges between E. stenonis vireti (Saint Vallier, 2.5 Ma), E. stenonis olivolanus (Olivola, 2.0-1.9 Ma) and E. stenonis stenonis (1.9-1.8 Ma), which include the variability of the other two subspecies E. stenonis guthi (2.3 Ma) and E. stenonis pueblensis (2.2 Ma). These results support the hypothesis that all subspecies of Equus stenonis may in fact represent a single polytypic species. Nevertheless, E. stenonis senezensis differs from the other subspecies, for its more slender metapodial IIIs. The morphological and morphometric analyses of skulls, mandibles, maxillary and mandibular dentitions have revealed some interesting relationships between North American Equus simplicidens (Hagerman Quarry, S. Idaho, 3.3. Ma.), an early Equus species from Kenya, Equus koobiforensis, and the extant Grevy’s zebra, Equus grevyi. Our study suggests that Equus stenonis is related to modern zebras and perhaps asses.

Evolution of Crown Height in Holarctic and African Protohippine and Hipparionine Horse

Leads: R.L. Bernor and C. Janis

We have undertaken a study of the evolution of 97 species Protohippine and Hipparionine horses (subfamily Equinae) of North America, Eurasia and Africa between 17 and 1 Ma. As an estimate of body size, these horses range between 93 and 170 mm in cheek tooth row length (P2-M3). We report maximum crown height for these species but make the necessary adjustment for size by calculating Hypsodonty Index (HI = maximum unworn crown height/M1 length). Hypsodonty indices start as low values in Merychippus primus (= 1.2), M. calamarius (=1.3) and M. insignis (= 1.4). North American species of Cormohipparion range in HI between 1.7 and 2.3, North American “Hipparion s.l.” ranges between 1.6 and 2.2, Neohipparion between 1.8 and 2.9, Pseudhipparion between 2.2 and 3.8. Old World hipparionines first appear between 11.4 and 11.0 Ma. The most primitive taxon Cormohipparion sp. from Pakistan had an HI of 2.03, Turkish Cormohipparion sinapensis had a slightly elevated HI of 2.25 and North African Cormohipparion africanum increased HI to 2.52. The Hippotherium clade, dominant in the late Miocene of Europe, retained a relatively conservative crown height of 2.01 to 2.42. Hipparion sensu strictu, a distinctly Eurasian clade had HI ranging from 2.35 to 2.73. Eurasian and North African Cremohipparion had HI ranging from 2.37 to 2.79. “Sivalhippus complex” clades of Sivalhippus, Eurygnathohippus, Proboscidipparion and Plesiohipparion first appeared at the end of the Miocene and dominated Eurasian and African faunas. They underwent significant size increases in the Plio-Pleistocene. Sivalhippus ranged in HI from 2.0 to 3.23 and this was influenced greatly by the varying size of its species, with the largest species S. macrodon having the lowest HI value. Plesiohipparion evolved elevated HI indices ranging from 2.87 to 3.45. Proboscidipparion evolved very large size with HI ranging from 3.06 to 3.29. African Eurygnathohippus had HI from 2.16 to 3.0. The endemic Chinese taxon Shanxihippus dermatorhinus had an HI of 2.81. In all lineages we have reviewed there is a strong general trend of increased HI through the late Miocene and Plio-Pleistocene with the greatest HI being in later and larger more derived forms. Old World hipparions evolved diverse lineages that retained their size (Hippotherium, Hipparion s.s.), diversified into larger and smaller forms (Cremohipparion) and underwent a general increase in size phyletically (Sivalhippus, Eurygnathohippus, Plesiohipparion and Proboscidipparion). North America had a strikingly greater diversity of equids per locality (as many as 6-8 in the early late Miocene, but fewer in younger localities) whereas the maximum diversity of Old World hipparions ranged from 1-3 per locality. We recognize that Old World Hipparion s.s. had a relatively low diversity including H. gettyi – H. prostylum – H. dietrichi, H.campbelli and H. hippidiodus. Current evidence suggests that North American “Hipparion s.l.” including H. shirlyae, H. forcei and H. tehoense evolved convergently with Old World Hipparion s.s.